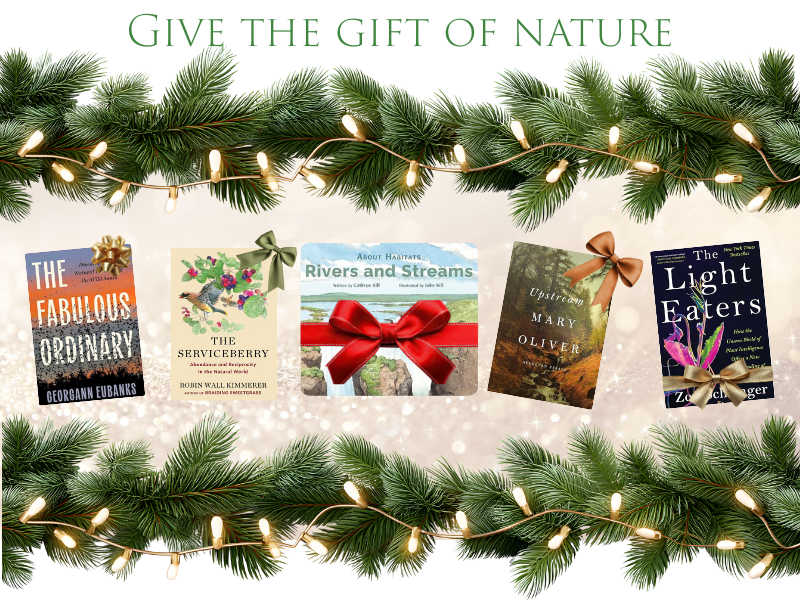

SFC's Top Five Reads for 2025

If you’re looking for a great read this holiday season, check out our top five picks for 2025. Read our reviews below.

The Fabulous Ordinary. Discovering the Natural Wonders of the Wild South by Georgann Eubanks, with photographs by Donna Campbell

Writer Georgann Eubanks invites us to join her and photographer Donna Campbell as they travel across seven southeastern states: Alabama, Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee. Their purpose? To witness what she calls “common events that we had never experienced up close.”

These events are “common” in that they happen every year in these places. To many—perhaps most—of us, they are anything but common. They are definitely fabulous, though.

Eubanks records her experiences, sharing her excitement and awe at encountering sandhill and whooping cranes, alligators, acres of blooming dimpled trout lilies, toads, raptors, migrating purple martins—to name but a few. Along the way, she sketches a brief history of a place, talking with local guides, botanists, and naturalists about their work with a particular animal or plant. An excellent bibliography, arranged by chapter, offers the opportunity to learn more.

Readers will feel as if they are alongside Eubanks on night walks in Alabama and North Carolina; or watching the careful banding of newborn kestrels and tiny screech owls in Virginia; or learning about river otters in Florida and alligators in Georgia. It’s impossible not to feel the thrill of seeing fireflies in the Smokies when she writes: “As darkness arrived . . . the light show began. It took a while, but the numbers of fireflies gradually increased, building their themes of light, like the first movement of a symphony.”

Each chapter—and there are 15—takes us on a different adventure. Following Eubanks’ lead, readers could design an itinerary that would introduce them to the natural wonders we read about in these pages. Just as the author’s trip didn’t occur in a single season, yours could be done over time. While there is still time.

“Everyone of us,” she says, “including future generations, deserves to experience the fabulous ordinary. An encounter with an elk—once lost to our region and now reintroduced—helps us see the past more vividly and understand the challenges of the present.”

Sometimes we are armchair travelers, but then, if we’re able, it’s time to put down the book and take that road trip. Then we’ll understand what Eubanks means when she writes about the blue ghost firefly: “I know it was too late in the season for blue ghosts, but then I saw one, ten feet away, faint and pale, rising from the duff, then another and another. They stayed lit for long stretches. I could hardly contain my delight. Why didn’t I ever look before? Because I didn’t know before.”

The invitation to be open to the world, to experience some part of it, is there. Don’t miss your chance.

The Serviceberry. Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World

by Robin Wall Kimmerer; illustrated by John Burgoyne

In her latest book The Serviceberry, Kimmerer, best-selling author of Braiding Sweetgrass, describes the abundance and reciprocity of the serviceberry tree in the natural world. In 105-pages, Kimmerer compares the interdependence among plants, animals, and soil to the human “gift economy,” in which goods and services circulate without expectations of compensation. Its currency, she says, are gratitude and reciprocity.

Kimmerer is member of the Potawatomi Nation, a storyteller, botanist, and professor at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry. She introduces us to the serviceberry (Amelanchier) family. Serviceberries are known by a variety of names: Juneberries, Sugarplum, Sarvis, Shadblow, and Shadbush.

These trees provide year-round interest with beautiful white blossoms in the spring, delicious fruit in the early summer, colorful foliage in the fall, and interesting bark in the winter. The fruit can be eaten fresh, cooked in pies, or preserved in jams and jellies. An added bonus: the tree is deer resistant.

With Kimmerer’s rich and evocative prose, readers enter a world that supports and is supported by the serviceberry. The life cycle of this tree is symbolic of a gift exchange. The serviceberry gives and receives from the surrounding environment.

“Maples gave leaves to the soil, the countless invertebrates and microbes who exchange nutrients and energy to build the humus in which a Serviceberry seed could take root, the Cedar Waxwing who dropped the seed, the sun, the rain, the early spring flies who pollinate the flowers, the farmer who wielded the shovel to tenderly settle the seedlings. They are all parts of the gift exchange by which everyone gets what they need.”

Likewise, human communities can exchange goods and services without expecting compensation. For example, if someone has an excess of produce, such as veggies from the garden, they may share with neighbors or leave them on the side of the road with a message “free veggies.” We often think of zucchini as an example of back-yard garden plants that produce more than enough for one family waiting as a gift to anyone who needs or would like some. In this gift exchange, there is no need to amass “things.”

Regarding front-yard giveaways, Kimmerer asks, “Is this an economy?” She thinks it is a system of redistribution of things based on abundance and the pleasure of sharing. Someone says “I have more than I need” and gives some away. Giving begets giving—and the gift stays in motion.

So much to think about in this small book. Enjoy!

About Habitats: Rivers and Streams by Cathryn Sill; illustrated by John Sill

This lovely, quiet book is a perfect way for young readers to learn about the waterways that are the source of life on earth. The book opens with an illustrated glossary describing parts of a river basin. The format is simple: a single sentence on the left side of the page, an illustration of that sentence on the right. For example, the sentence “Rivers provide food and shelter for many kinds of animals,” is followed by an illustration depicting a half-dozen animals found on the Altamaha River.

The illustrations offer glimpses of animals, like salamanders and turtles, living in or near creeks and rivers, as well as those like torrent ducks in the Andes that live in mountain streams. The book also includes a bibliography, a few websites about rivers, and an afterword that offers more commentary about the illustrations.

This summer, encourage your children to read the book, or read it to them. Then take them to a nearby creek, like the South Fork, for an up-close exploration of the creek and its banks. Teach them about its origins in Tucker and how it travels west to Atlanta where it joins with the North Fork to create Peachtree Creek. The Peachtree empties into the powerful Chattahoochee River, the source of metropolitan Atlanta’s drinking water.

3-year-old Mateo, a South Fork trail explorer, flips through the beautiful illustrations at bedtime.

Bring a picnic lunch and stop at one of the many destinations bordering the South Fork, such as Friendship Park in Clarkston, Mason Mill or Zonolite parks near Emory, or Armand Park in Atlanta. You might be lucky enough to spot turtles, ducks, or a great blue heron along the way. Have fun!

Upstream

Selected Essays by Mary Oliver

Readers of Mary Oliver’s poetry are familiar with her clear observations of the natural world. Fewer, though, may be acquainted with her essays. Upstream, published in 2016, offers up nineteen essays, three of which appear for the first time in this slim volume.

Some essays focus on writers such as Emerson, who profoundly influenced her thinking. Others detail her attentive explorations of her New England landscape and its non-human inhabitants. She writes about frogs, foxes, snapping turtles, owls. One essay, “Swoon,”describes in detail her hours-long observations as a spider snares and feeds on a cricket in its web. It’s a difficult, unsettling read. Her acute observations of the workings of the natural world, recorded daily in her notebooks over many years, are the sources of her glorious, precise poems.

“All the questions that the spider’s curious life made me ask I know I can find answered in some book of knowledge,” she writes. “But the palace of knowledge is different from the palace of discovery, in which I am, truly, a Copernicus.”

Indeed, she was. Through all her writings, Oliver, who died in 2019 at age 83, encourages us to pay attention. Most of us will not achieve or aspire to her degree of devotion, but we can at least learn from what she saw. Find this book in a public library or local bookstore. As she once said, "The world did not have to be beautiful to work. But it is.” Take a walk and notice all you can.

The Light Eaters. How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth by Zoë Schlanger

Be prepared to have your mind blown as you read this brilliant book. Schlanger, an award-winning science writer, meticulously examines how plants negotiate their environments. She pores over years of scientific plant research, some going back to Darwin, and interviews dozens of scientists to find out what plants are and what makes them tick.

It’s complicated, to say the least, but Schlanger is up to the challenge. She writes, “[Plants] make food out of light and grow rooted to one spot, spending decades or centuries probing their environments for sustenance. Their way of life is so alien as to often preclude them in our imagination from even having a way of life.”

Across eleven packed chapters, she examines a wide range of topics— plant behavior, kinship, vision, touch, hearing, mimicry, plasticity, communication, socialization, memory. It’s impossible to do justice to all that she uncovers, but Schlanger raises questions early on that help guide us through her inquiry.

“How does something without a brain coordinate a response to any stimuli at all?

How does information about the world get integrated, triaged by importance, and translated into action that benefits the plant?

How can a plant sense its world at all, without a centralized place to parse all that information?”

And Schlanger asks whether that the entire plant could, in fact, be its brain. This intriguing question comes up often over the course of her years-long work.

She faced resistance from botanists wary of sensationalism and reluctant to use terms like “plant behavior” or “plant intelligence.”

“The resistance by scientists to scientific discovery is a known fact; it serves as a bulwark against quackery. But it also often misses or delays actual discoveries,” Schlanger writes.

A researcher she visits in Berlin tells Schlanger, “Obviously, plants don’t have brains in the usual sense. But look what they do. They take information from the outside world. They process. They make decisions. And they perform. They take everything into account, and they transform it into a reaction. And this to me is the definition of intelligence.”

Another botanist tells her, “What I’m talking about is not academic intelligence. It’s biological intelligence. Every organism on this earth acts intelligently.”